World Game: Yang Hansen’s Impact Reaches Beyond Portland

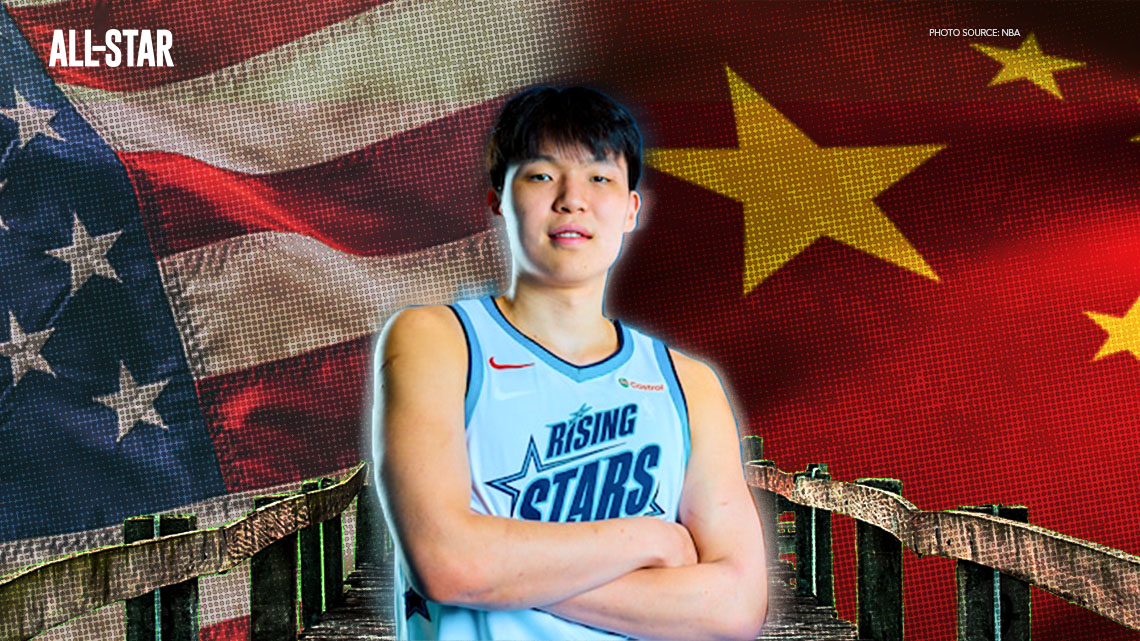

When the final buzzer sounded for the opening game of the Rising Stars event at NBA All-Star Weekend, the loss, to some degree, felt secondary. In the quiet that followed, Yang Hansen leaned into the moment the way he has approached his entire rookie season: carefully, thoughtfully, with an eye toward something bigger than a box score.

“I’m learning basketball in the world right now and in the NBA,” he said through a translator to a group of media, quite a number of them from Asia. “I will try to learn as more as I can and carry them back to Asia or China.”

The line landed with more weight than the game. For Yang, the NBA is not just a destination. It is a classroom. And for a league that has long searched for ways to reconnect and deepen its roots in China and across Asia, his presence represents something both practical and symbolic.

The 20-year-old’s journey to this stage has already been prolific. The 7-foot-1 center from Zibo, Shandong rose through the CBA with the Qingdao Eagles before becoming a first-round pick of the 2025 draft, selected 16th overall by the Portland Trail Blazers.

In a league that had not seen a Chinese player drafted that high since Yi Jianlian was taken ninth by Milwaukee in 2007, the reaction was immediate and global. In China, social feeds surged. In Portland, merchandise sales reportedly spiked dramatically compared to the previous year. Blazers content on Chinese platforms saw major growth. A rookie who had yet to log a regular-season minute was already shifting business metrics across the Pacific.

That commercial surge is only one layer of his impact. The NBA’s relationship with China has always extended beyond hardwood results. From Yao Ming’s rise to preseason games played overseas, the league’s footprint in Asia has been both cultural and economic. Yang’s arrival reopened that conversation in real time. Summer League games featuring him drew outsized attention. Fans traveled, watched at unusual hours, and filled timelines with clips of touches, pass, smiles.

Just recently, an NBA G League game featuring Yang with the Rip City Remix was televised at two in the morning in China. It drew at least 200,000 viewers.

On the court, the learning curve has been real. Through the early stretch of his rookie season with Portland, Yang has played limited minutes, roughly seven to eight per night, averaging modest scoring and rebounding (2.2 PPG, 1.6 RPG) numbers while adjusting to NBA speed and physicality.

His shooting percentage reflects the unevenness typical of young bigs finding their rhythm against veteran defenders, especially those from outside the United States. It doesn’t help he’s playing behind another recent young Blazers big man draft selection, Donovan Clingan, who’s seen improvement this season. Portland has used the G League as a development runway, giving Yang longer stretches to explore his game, and he has flashed why scouts were intrigued. There is touch around the rim, a willingness to pass, and a feel for the game that led some evaluators to loosely compare his vision to modern playmaking centers.

The Rising Stars selection signaled that the league sees him as more than a marketing storyline. It was recognition of potential. Even in defeat, Yang’s composure stood out. He did not speak about frustration.

He spoke about responsibility.

“There’s a lot of talented kids in Asia and different countries,” he said. “They will all try to reach their dreams and make it to the NBA.”

That perspective reframes his rookie season. His stat line is one story. His symbolism is another. In gyms across China, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and the rest of Southeast Asia, young players are watching his progress. When Yang checks into a game in Portland, it resonates thousands of miles away. When he returns to the bench, those same viewers stay.

His third quote may be the most revealing.

“We’ll see more and more Asian faces in the NBA court.”

It is both prediction and promise. For decades, Asian representation in the NBA has come in waves. Wang Zhizhi made early ripples. Yao Ming opened doors. Filipino-Americans are turning into legitimate contributors. Others followed in shorter arcs. During the Basketball without Borders camp in Los Angeles for All-Star Weekend, there are two representatives each from China and Japan, and a handful more from Australia and New Zealand.

Yang is attempting to establish something steadier, not just as a pioneer but as part of a larger cohort that sees the league as accessible, not abstract.

The NBA exports entertainment and opportunity. Yang wants to import knowledge and raise standards at home. In that sense, he is not just representing China in the league. He is representing the league to China.

The business implications are obvious. The cultural implications are deeper. In a time when global sports often intersect with politics and diplomacy, basketball remains one of the most universal languages. A rookie center fighting for minutes in Portland can become a bridge without ever intending to be one.

Can he add strength? Can he adjust to NBA pace? Can he carve out a consistent role? Those are basketball questions with basketball answers.

But his quotes after the Rising Stars loss suggest that he is measuring success differently as well. He is gathering experience, processing it, and thinking about who comes next.

In that way, even in defeat, Yang Hansen sounded less like a player discouraged by a single game and more like a student aware that he is part of something larger. The numbers will fluctuate. The minutes will ebb and flow. The cultural wave he rides may rise and settle.

He seems prepared for all of it.

And somewhere in Asia, another young player heard those words and believed them.